Gaa-Bizhiwebak

Our History

The Odawa inhabited Odawa Mnis or “Manitoulin Island” for many years prior to any other tribal settlements; Manitoulin Island has also been called “Ogemah Mnis”, the home of the ancestors as recorded by many Chiefs having been buried here. Prior to European contact, a confederacy of Anishinabek tribes composed of the Odawa, Ojibway and Pottawatomi controlled the Northern Great Lakes areas including Manitoulin Island.

In documented records from 1610, the Anishinabek established first contact with the French via Étienne Brûlé along Georgian Bay whom was a part of the Samuel de Champlain expeditions on the North American frontier. In the summer of 1615, Samuel de Champlain met some 300 Odawa warriors near the present-day Collins Inlet and Beaverstone Bay area, just west of the French River. These encounters began a trading relationship between the Anishinabek and French or “Wemtagoosh”.

Years later in 1648, a French Jesuit named Joseph Antoine Poncet arrived on Manitoulin Island and set up a mission for the Anishinabek. Father Poncet was the first European visitor to take up a brief residence on Manitoulin Island in which he endured a severe winter on the Island. The village of Wiikwemkoong during his time was further inland past the southwest shore of Wiikwemkoong Bay along the banks of a small river. This location would be near the Kimewon residence in Murray Hill, ON. By the mid seventeenth century, a small Roman Catholic mission was also established at this location. Some local Anishinaabek would attend this mission through a small river system which connected South Bay with Wiikwemkoong Bay via one portage located also in Murray Hill near the present day Manitowabi residence.

British expansion continued west and began to come into proximity of the Great Lakes region due the Hudson’s Bay company controlling the fur trade within the Hudson’s Bay drainage basin. Encroaching French and British Colonies collided in trade and territorial conflicts which began the Seven Years War (1756-1763). The Anishinabek had invested an alliance through ‘Gift Diplomacy’ with the French and allied with the Wemtagoosh during this period. Upon the defeat of New France, between 1760 and 1763 the Anishinaabek, led by an Odawa named Pontiac, had maintained their sovereignty through warfare with the British also known as Pontiac’s War. Following this war, the British wanted to end all conflicts with the Anishinabek of the Great Lakes and all other neighbouring tribes. This would lead to the 1763 Royal Proclamation by Britain’s King George III.

The 1763 Royal Proclamation document would instill protection of “Indian Lands” by the British Crown and that the Crown identifies the lands the Indians occupy is rightfully theirs. This also sets out the treaty-making process that the British must abide by to gain access to any territory the Anishinabek occupied.

The following summer in 1764, a great diplomatic council was held at Fort Niagara which saw Chiefs and representatives of more than 24 nations that resided in the Great Lakes region, including the Anishinabek of “Odawa Mnisiing”. This treaty reaffirmed the relationship between the Anishinabek and the British Crown, through the exchange of not only gifts but also lasting promises embedded in Wampum.

When the war of 1812 broke out, the British needed the help of the Anishinabek due to their extensive knowledge of the land and waters. About 2000 Anishinabek warriors from north of Lake Superior, Lake Huron and Odawa Mnisiing volunteered their service to not only oblige their alliance with the British, but to protect their territory as well from American encroachment. One of the most notable warriors from Odawa Mnisiing was Chief Mookmaanis of Wiikwemkoong. Due to his efforts in the war he was awarded a Silver Sword on behalf of the British Crown.

With the end of the War of 1812, the Anishinabek of Odawa Mnisiing would return to their territory to live in peace. However, the arrival of more European settlers looking for a fresh start in North America would begin another territorial engagement.

In 1830, US president Jackson issued the ‘Indian Removal Act’, leading to the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, which was ratified in 1835. During this time the U.S. government forced the Pottawatomi and neighbouring tribes to sell their land. More than 3,000 Anishinabek consequently left their homelands and Pottawatomi families began to arrive in Canada around this time.

Concurrently in 1836, the main objective of the Bond Head Treaty was to initiate the migration of Upper Canada Indians to Manitoulin Island where they could live with the Odawa in their territory on Lake Huron and its Islands, free from the influences of the encroaching white civilization.

“I consider, that from their facilities, and from their being surrounded by innumerable fishing islands, they might be made a most desirable Place of Residence for many Indians who wish to be civilized as well as to be totally separated from the Whites; and I now tell you that your Great Father will withdraw his Claim to these Islands, and allow them to be applied for that Purpose.”

– Sir Francis Bondhead August 9th, 1836.

Many Upper Canada Indians did not migrate to Manitoulin Island as intended by the Crown. Therefore, in 1862, the McDougall Treaty was initiated and signed. This treaty targeted the surrender of lands on Manitoulin Island.

Wiikwemkoong did not sign the treaty and vehemently opposed any treaty making with the Crown, and thus it became known as the Manitoulin Island Unceded ‘Indian Reserve’.

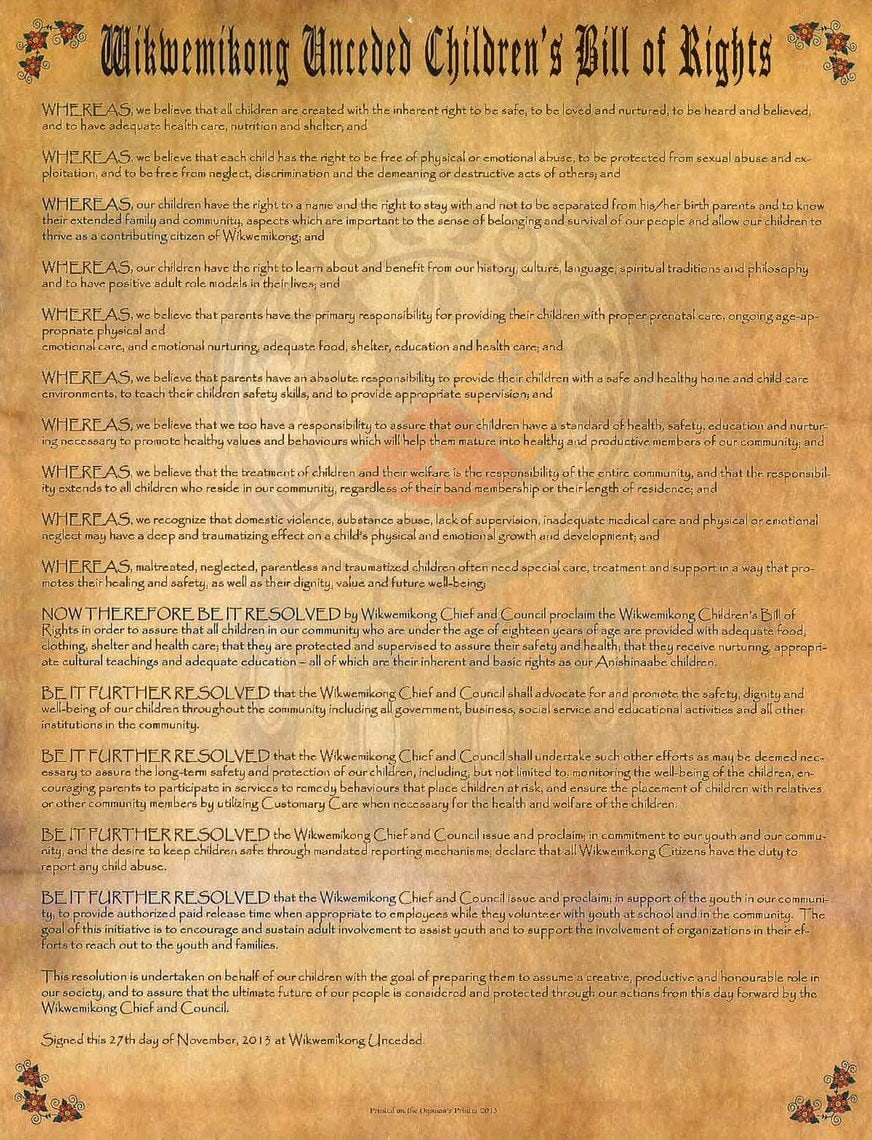

In 1968, an amalgamation took place among three bands: Manitoulin Island Unceded Indian Reserve, Point Grondine and South Bay. This amalgamation created the Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve. In 2014, the Constitution- Wiikwemkoong G’chi Naaknigewin was ratified, birthing a renewal of pride in our unique political and legal history.

The people of Wiikwemkoong take great pride in the living history, culture and language of their community and in the diverse traditional arts that are present. In 2006, the citizens of Wiikwemkoong formally implemented a community-based Anishinaabemowin Language Strategy to retain our language for all future generations. It was also during this time that the Department of Canadian Heritage designated Wikwemikong as one of several Cultural Capitals of Canada.